In honor of Matt's new horror release, Bennytown, I'm asking him a few questions. And with no false modesty, I think my insider knowledge of both this terrifying book and the psyche of its creator allowed me to coax forth some pretty interesting answers.

See for yourself:

FJRT: Tell us about Benny the Bunny himself, the icon and mascot of Bennytown. Within the world of the novel, he’s a fictional character whose likeness is all over the park. How was he created, and what is he like in his own doubly fictional world where he’s real?

MC: Benny the Bunny… wow, he and I go back. He was the subject of a lot of my horror-based writing throughout a lot of my early attempts in the genre, an evil, malevolent Barney like figure back when Barney was a character who particularly annoyed me (can you tell I’m a 90s kid?), though for the record I hold no ill will towards now. Over time, Benny evolved more into an amalgam of famous cartoon characters and ubiquitous cultural icons as a satire of ever-present media creations, and has become a lot more fun to play with because of it.

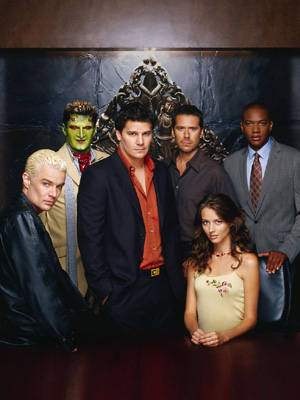

In the world of Bennytown… Benny the Bunny is the world’s most popular and recognizable cartoon character, the icon of the Dorian Studios media empire. He’s a green bunny rabbit who wears overalls and white gloves. Personality-wise he’s distinctly mellow and friendly, always with a kind word or a wise story, always welcoming you to sit on his front porch in Happy Hollow so he can play you a song about friendship on his banjo. Benny the Bunny wants to be everybody’s best friend, especially to those who have no friends. Benny believes in you.

FJRT: You’ve written young adult horror in the past, and Noel, the protagonist of Bennytown, is a teenager, but you chose to write his story for a more general adult horror audience. What factors went into that decision, and how is the book different from what it might have been if you’d taken a more teen-focused approach?

MC: From the start, I knew that I wanted Bennytown to be an adult oriented horror novel, because that is the type of horror that I’ve read for about as long as I can remember. Stephen King was very much a part of my coming into being as a horror fan, and I’ve wanted to walk in his footsteps for a very long time you could say.

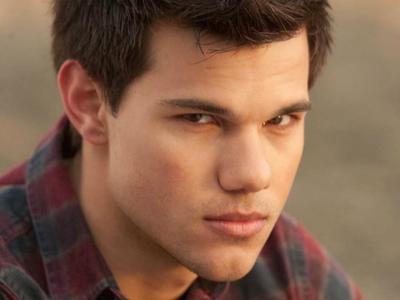

But why would I make Noel sixteen? Well, a lot of the decision-making on that front simply came from life experience. I wanted to write this story from the naïve perspective of a new hire at Bennytown, and having actually been a new hire at a theme park once upon a time back in the dark ages when I was sixteen, it was the kind of story-telling fit I knew that I could do some justice to. It gives Noel less life experience, less a frame of reference for him to be able to tell what is and isn’t normal in a job like this, and more for the sinister forces behind the park to play with in his psyche.

If I was going to write this for a more teen based approach… I think I wouldn’t go quite as far as I went in some of the darker portions of this book, because I get pretty twisted at points. I know YA has grown a lot since I last read it, but I also know that I went to some dark and uncomfortable places in this book that I only stepped into here hesitantly. I also know that it would have affected how I wrote the ending, but without going into any spoilers I think I’m just going to leave that one where it is.

FJRT: You’ve talked elsewhere about how especially long the process of developing Bennytown was. How much did the final version end up differing from your initial plans for the story?

MC: Like almost everything I write, the first draft of Bennytown was rather long and meandering, and through various editing phases I wound up cutting close to 30-40,000 words to make it a tighter, more coherent story. A lot of things wound up getting cut in the process, a couple supporting characters (including Noel’s childhood best friend, who was quite important to the plot at first), some scene blocking that had to be adjusted, even a whole subplot about the horrible goings-on at Lost & Found. Once it got into my editors’ hands, it began to change even more, until it reached its current state, which I’m quite happy with. Things change from draft to draft, and sometimes that’s for the best.

FJRT: Bennytown alternates between Noel’s narrative and vignettes from the park’s sixty-year history. Why did you decide to show us parts of Bennytown’s backstory directly, rather than through Noel’s eyes?

MC: Part of this was simply because I wanted to weave a tapestry that was larger than just one character’s perspective would allow for. To get in a lot of the information I wanted about the park while strictly using Noel’s perspective would have required a lot of random information dumps, which would have felt inorganic in the limited, even naïve perspective I wanted to create with Noel. He can’t see everything, but the things he can’t see often have a way of affecting him.

As well, by looking into these little vignettes from over the park’s 60-year history, I wanted to help breathe life into Bennytown itself. The park itself is almost the second main character of the book next to Noel, and by showing it throughout the years, we get a chance to see that it has existed even without Noel and didn’t just spring to life the moment he popped onto the scene as a character.

And, from a simpler, geekier level, I am a huge fan of both history and worldbuilding, and getting to visit the park throughout the decades was a fun way of getting to put my worldbuilding designs for this story to use.

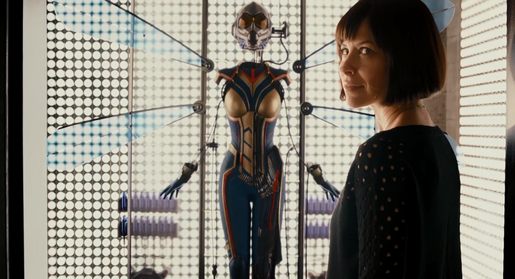

FJRT: It’s me you’re talking to, so I have to ask, can you tell us a bit about the ladies of Bennytown and what it was like writing them?

MC: While I can’t go into tremendous detail about my characters without giving away some spoilers, on the whole I’m quite proud of the women of Bennytown. Characters like fellow employee Garcia, restaurant manager Kathleen, park heiress Elle Dorian and Noel’s girlfriend Olivia are more than just supporting characters for Noel’s journey. These are people who have their own stakes in what happens in Bennytown, their own histories and issues with the park and their own goals. This being a horror story, I’m not going to go out and promise them all happy endings, but I like to think I managed to make them all fleshed out characters who are doing everything they can to make it through this torment.

What it was like writing them… well, honestly it was like writing any other character in the story. I try not to differentiate too much between how I write my male and female characters, since everyone is a character first. I’m not saying that there are no differences, because different people with different backgrounds will have different life experiences that inform who they are as characters as well, I won’t deny that, but I want to try to give everyone the same level of developed backgrounds and agency within the story.

FJRT: Would it be fair to say that you’re a feminist, but that your lead characters can’t always say the same? How would you characterize Noel’s morality, and how is it different from your own? How does it feel to write those differences?

MC: I completely and utterly identify as a feminist, but that doesn’t mean the characters I write always are. A lot of stories I write are characters exploring their worlds and themselves, either confronting their personal demons or succumbing to them, and sometimes that doesn’t take characters to the greatest places in their minds or biases. I like to see characters succeed and get over their own issues, but it all depends on what works best for the story.

Noel’s morality is limited by his experiences. He’s a sixteen-year-old kid raised in white bread suburbia, which has given him a very limited worldview. He’s childish in many ways, knowing that he has to grow up and somewhat looking forward to that change, but also wanting to hold onto his childish side. In a lot of ways, it was like looking back into my own teenage years when I was a much less happy person, and much more sheltered from the wider world. It was unsettling digging into my past for these elements of a character that I’ve done my best to grow out of, but in this story it felt right to revisit those demons to better have an understanding of a character dealing with similar demons. Noel and I are very different people, and he has a lot of rougher edges than I ever did, and he is manipulated into making some bad decisions I know I never would have, but I still have a lot of sympathy for a lot of what he is put through.

FJRT: Would you say Bennytown itself has a “moral,” and how do you feel about morals in horror in general?

MC: While I wouldn’t use the word “moral” per se when discussing Bennytown, one of its major themes is growing up. Noel is confronted by a world and a particularly bizarre set of circumstances that have him battling between the realities of growing up and what he thinks it means to “be a man” in the limited societal context that he has for that phrase, while still wanting to hold onto his childhood as a life preserver. It’s a battle we all must go through in life in one form or another, and some of us handle it better than others, and that is definitely a conflict that Noel himself has to deal with over the course of the story.

As for morals in horror… I can go either way on the subject. The classic definitions of morality and morals popping up in horror as guides to tell people what to do and what not to do often come across as puritanical and misguided. It’s the subtle messages that we come to think of as clichés and tropes, the kinds of things you yell at characters for screwing up, those I find to often be the best morals to take out of horror.

Stick together with friends in the face of evil.

Don’t make fun of the unpopular kid. Or anyone, for that matter.

Always be prepared.

Turn on the damn lights.

Don’t be an asshole. Of any kind.

These are good morals to take out of horror, I’d say.

FJRT: In literature and film, hauntings are often tied to characters being unable to escape or let go of the past. Are these important themes in Bennytown?

MC: Oh, very much so. Bennytown is very much a patchwork of events that have happened and people who have passed through (and passed away in) the park. Bennytown’s past is inextricably tied to its present, a battle that is played out nightly in the park.

As for Noel, his past with Bennytown might leave him particularly susceptible to the evil forces at play. After a childhood tragedy, he credits frequent visits to the park with restoring his mental health, and he has a skewed view of Bennytown because of it. He forces himself into a position of being willfully ignorant of anything bad happening there and… well, I might have said too much already.

FJRT: In folklore, hauntings tend to revolve more around simple but striking images that only hint at a vague or changeable bigger story, like the Headless Horseman or Bloody Mary. Would any of Bennytown’s apparitions make good campfire legends in their own right? Which ones were the most fun to design visually?

MC: Oh yes, very, very much so. There are quite a few distinct spirits wandering the grounds of Bennytown, and though most of them are benign, occasionally chaotic entities, the leftovers of people who’d died in the park but were never allowed to move on, there are some bad ones who have really left an ugly mark on the park and wander around as nightmarish revenants.

Easily the one who gave me the most willies when writing the book is that of one of the park’s wandering costumed characters, Wilbur Walrus. Though seemingly a benign cartoon character, with soft purple skin and a loud Hawaiian shirt, the person behind the costume for Wilbur is an utter monster, a prolific child abductor and murderer who hid within Bennytown with the help of the park’s dark magics before his gruesome demise. Now he wanders the park as a grotesque, half-rotted beast, tormenting the story’s main characters and the ghosts of his victims that he keeps on a very short leash. He’s disgusting, unsettling, and was both fun and utterly repulsive to write for.

FJRT: Finally, if you had the chance to visit Bennytown as a guest (in non-pandemic times), would you do it? Why or why not?

MC: Dear god, no, lol. I mean, in the context that I created it for the story, Bennytown the theme park may well be “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth”, and I wouldn’t want to risk my health and soul just for a theme park experience, no matter how wonderful their attractions were. Now, even if it weren’t for the dark forces that run things behind the scenes, I still designed a lot of Bennytown to be a fairly obnoxious theme park, so I don’t imagine I’d be jumping into it anytime soon. Yeah, there are a few attractions I’d enjoy checking out… but at the end of the day I think the best way to visit Bennytown would be in the pages of this book, and not in person.

Besides, this way I don’t have to wear sunscreen or wait in line, a combination which will always get my vote.

For nearly sixty years, Bennytown has been America’s most exciting family theme park destination. Under the watchful eye of cultural icon Benny the Bunny, the park has entertained generations of children with its friendly atmosphere and technologically innovative rides. Park founder Fletcher Dorian’s dream lives to this day, with Bennytown acting as a beacon of joy and wonder, where magic is real and dreams come true.

Bennytown once saved sixteen-year-old Noel Hallstrom’s life, and to repay it, Noel has applied for a summer job. Though the work is messy and the hours are bad, Noel is happy to be a part of the Bennytown family, until he sees the darkness beneath the surface. Strange, mechanized mascots walk the park perimeter. Elegantly dressed cultists in wooden Benny masks lurk in the darkness. Spirits of the many who’ve died in the park roam freely, and every night the park transforms into a dark dimension where madness reigns and monsters prowl.

Noel is about to find out more about Bennytown than he ever wanted to know, and that its darkness might have designs on him…

Plan your visit today:

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

IndieBound

Kobo